Grant believed amnesty-not revenge-would put the country on the path to healing. There would be no attempt to round them up and try them for treason. In writing out the terms for unconditional surrender, Grant added two sentences that allowed the soldiers of the Confederate army to return to their homes. Grant received a new epithet: savior of the Union.

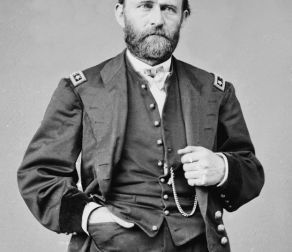

Ulysses s grant jr series#

Grant prevailed again in the Overland Campaign, a bloody series of engagements that included Cold Harbor, but at a cost of more than 38,000 casualties and a good deal of Northern morale.īut ten months later, on Palm Sunday, April 9, 1865, Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House, ending the Civil War. Soon Grant, who disdained the pomp of uniforms, sported three stars on his shoulder, only the second man to hold the rank of lieutenant general since George Washington. “He fights.” There were more victories ahead: Vicksburg, Chattanooga, and Missionary Ridge. After his victory at Shiloh in 1862 left 13,047 soldiers dead or wounded, Abraham Lincoln was urged to remove him. Lee’s 59,000, Grant lost the thirteen-day engagement and suffered 12,737 casualties, leading to his nickname “the Butcher.” It also wasn’t the first time Grant’s losses caused consternation. Despite having 108,000 troops to General Robert E. He looks off into the distance, his eyes made old by the horrors he’s seen and ordered.īrady’s photo was taken during the Battle of Cold Harbor, one of Grant’s worst outings. His stance is defiant, almost cocky, yet he doesn’t engage the camera. Dust covers his uniform and boots, signaling that he’s no armchair general. Grant stands with his right arm resting against a tree, left hip and arm thrust forward, and hat tipped slightly back. Mathew Brady managed to capture Grant’s essence in an iconic photo taken in June of 1864. He was the closest thing America had to an honest-to-goodness hero. The attention wasn’t for the United States, but for him. “I appreciate the fact-and am proud of it-that the attentions I am receiving are intended more for our country than for me personally,” he wrote. He had worked hard during his presidency to resolve grievances that had lingered from the Civil War. Grant characterized the sentiment as a sign of the resumption of friendly relations between the United States and England. There were receptions and parties, and even quiet moments, like breakfast with Matthew Arnold, Robert Browning, and Anthony Trollope. Queen Victoria invited the Grants to stay at Windsor Castle. Invitations poured in from towns and individuals hoping to host him. “I hope you will continue to write often because when your Ma is a week without letters from her worthless children she grows uneasy,” he wrote Buck.

Grant wrote to his sons, Fred and Buck, whom he chided. It wasn’t uncommon for Grant to arrive in a major city and find Badeau’s latest chapter ready for his commentary. He corresponded with General Adam Badeau, his former staff officer who was writing a military history of the Civil War. He wrote to his old Civil War colleagues generals William T. For Grant’s take on things, you have to go to his letters. Young’s account of their travels, eventually collected into two volumes, reads like a gossipy travelog. Grant agreed, understanding the value of keeping his name in the press. James Gordon Bennett, Jr., the publisher of the Herald, was betting Grant’s adventures would make good copy and asked to send Young along. The Grants left Philadelphia in mid May, joined by Jesse, their youngest son, and John Russell Young, a veteran reporter from the New York Herald.

Hayes, who’d barely squeaked into the White House, a chance to govern without reporters constantly running to his predecessor for comment. By leaving the country, Grant also believed he would be giving President Rutherford B. He’d turned down the chance to run for a third term.

He didn’t have a plantation to run like Andrew Jackson, nor did he want to design buildings or found a university like Thomas Jefferson. The trip also solved the immediate problem of what Grant, a spry man of fifty-five, should do after leaving the White House. After eight years in the White House, with no ancestral home to return to, Grant and his wife, Julia, decided to indulge their wanderlust and take a long-desired tour overseas. Liverpool was the first stop on Grant’s two-and-a-half-year trip around the world.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)